Robert Wortmann: Welcome to a new episode of Breach FM! Today, we have a slightly different setup. Unfortunately, Kim has once again become involved in an incident response case, which began at 9:21 AM. We had scheduled recording for 9:30 AM, so the timing was once again perfect. However, this once again demonstrates that the topic of incident response makes life unpredictable and likely entails a lot of work professionally. Kim sends warm regards to everyone. Hopefully, he’ll be back with us in the next episode. As I mentioned last time, it would be a bit lonely by myself. I’ve had the idea of inviting a highly esteemed guest for a while now, and finally, the time has come. Philipp, it’s great to have you here today. Would you like to introduce yourself briefly to our listeners? Who are you and what do you do? And why are we sitting here together today?

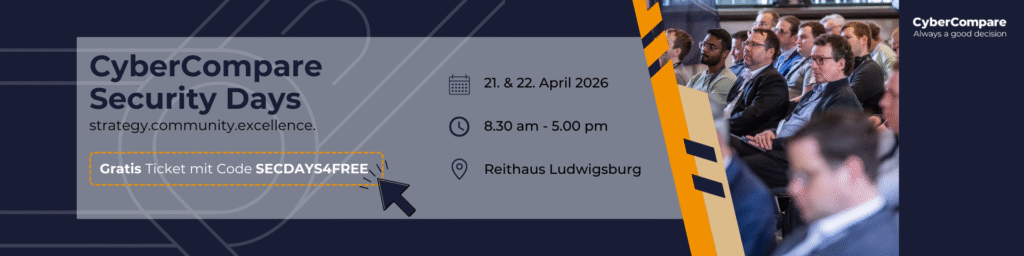

Philipp Pelkmann: Thank you for the invitation, Robert, and Kim, I wish you success simultaneously. My name is Philipp Pelkmann, and I work at Bosch CyberCompare, which I co-founded. Some listeners may already be familiar with my name, and perhaps some new ones will join today. How did we come together? That happened a few weeks ago when you conducted a fantastic interview with Ben Bachmann. We have a close collaboration and have known each other for some time. That’s how I became aware of the podcast, and I was very pleased to be invited to join here today.

Robert Wortmann: Yes, exactly, that fits very well. We’ve already discussed this in the previous podcast episodes. How do companies actually find the right solutions for their requirements? In recent years, we’ve noticed – and this has nothing to do with our perspective as manufacturers, Kim and I do work for the manufacturer, but that’s not the focus of this podcast – that requirement catalogs are often not very meaningful. Almost every manufacturer can confidently answer ‘Yes.’ But after some time, it becomes clear that the manufacturer doesn’t fit and has promised too much. Today, we want to talk about how that can happen and how one should be cautious in the selection process. Often the problem lies in the requirement analysis, and the manufacturer can only respond to the questions asked. Today, we want to discuss how platforms like Bosch CyberCompare can help find the right provider. We want to talk about our practical experiences – dos and don’ts as well as one or two stories where things went wrong. It will be an interesting exchange. CyberCompare is an exciting topic. I have a long history with Bosch, so I know that products there are thoroughly tested, sometimes even too thoroughly in the past. It took a long time for decisions to be made, but in the end, there was no chaos of applications or systems like at other companies of this size. So, my first question: What was the idea behind Bosch CyberCompare? How did it all develop? What is the story up to today?

Philipp Pelkmann: Yes, a very interesting question. I’ve been with the company for 18 years now, starting at Bosch in 2005. Initially, I was a business informatics specialist and began my career as a software developer at an agricultural machinery manufacturer in East Westphalia. Early in my career, I joined Bosch, where I worked in IT, including in plant IT in the Asia-Pacific region. There, I was heavily involved in topics such as digitization in manufacturing and Industry 4.0. Later, I moved to the Bosch corporate headquarters at Schillerhöhe, where I worked as an assistant to an executive and met my colleague and friend Jannis Stemmann. Together with him and Simeon Mussler, I co-founded Bosch CyberCompare. Jannis and I had similar roles, and our desks were side by side. The idea for Bosch CyberCompare emerged in a dialogue with a chairman of a Bosch business sector. We realized that cybersecurity was becoming increasingly important and that the market for solution providers for medium-sized enterprises was opaque. Although Bosch as a company is not classified as a medium-sized enterprise, many divisions operate similarly. It became clear that typical IT managers in medium-sized companies feel the pressure to address cybersecurity issues, even though they may not have access to large security teams. This situation requires a kind of intuitive action because most security budgets are part of IT costs and are under pressure. Often, there’s a lack of clear requirements, and manufacturers can only answer what’s asked. Therefore, we found it interesting to create a neutral marketplace for cybersecurity, helping medium-sized enterprises prioritize the right measures. In 2020, we validated the concept of Bosch CyberCompare through a market study and encountered a lot of openness from both providers and customers. There are many providers in the cybersecurity market, but no clear dominance. Our platform sees itself as a neutral marketplace for cybersecurity, helping customers understand their specific requirements. Some customers have clear ideas, while others need assistance with inventory and recommendations. We offer comparisons between different offerings and assess strengths and weaknesses. Bosch CyberCompare has been formally launched for about two years now.

Robert Wortmann: Something that has been on my mind for a long time. Why was Bosch CyberCompare developed under the Bosch brand? I saved this question for this podcast, although I could have asked it earlier, but it has always been an interesting point for me. When I dealt with Bosch, it was in completely different business sectors, and I wondered if this was a general strategy of the Bosch Group to diversify. Perhaps it was simply the intention to leverage the established name, which is not meant negatively. I would probably act the same way. I’m just curious about the idea behind positioning this project under the Bosch brand.

Philipp Pelkmann: The origin story is actually quite unspectacular. At the time, we, and still are, employees at Bosch. Even if I had worked for another company, and Jannis too, we would have tried to found the project based on our context. The idea arose as we analyzed the market and identified an interesting entry point. At that time, we were close to the Bosch management and were able to convince them through our dialogues, market study, and positive feedback from the initial customers that this idea had interesting business potential with high innovation power. Our colleagues were willing to support us and use the Bosch brand, which ultimately every startup needs – this so-called “unfair advantage.” If we had only appeared as CyberCompare, it would have been much more difficult to establish the first customer contacts. With Bosch backing us, it was different. We went in search of customers, approached partner companies deliberately, and explained, “We are developing this service right now. We don’t have many references yet, but we want to do good work.” That’s how we got into the market, and the Bosch brand particularly helped us with market entry. Bosch had no overarching strategic interests. It was an innovation that came from three Bosch employees and was supported by the Bosch management to validate the idea at the beginning. Due to the quick and good results, we were then allowed to further develop the project.

Robert Wortmann: How do you interpret the concept of “independent consulting”? I see this catchphrase on almost every website nowadays. I think in practice, everyone has a certain dependency, probably including you. The question always is, how does this dependency manifest itself? How openly do you deal with it, and how do you navigate this issue? How do you view this topic, and how independent are you actually? What are you, for example, dependent on in the market?

Philipp Pelkmann: Yes, that’s a really important point. It’s simply not possible for us to establish one hundred percent independence and neutrality. We’re not machines, but humans, and we’re influenced by many factors. That’s why it was important for us from the beginning not to enter into reseller or similar contracts with manufacturers or providers. We form partnerships, but without any pressure to place or sell specific products. That’s not our goal and never will be. In conversations with customers, I always emphasize that I couldn’t care less which manufacturer or provider they choose. Ultimately, the decision lies with the customer, not with us. What matters to me is that the customer feels comfortable with their decision. That’s our creed and at the same time, our moral approach, which is influenced by our work with manufacturers and information, but we try to be open about it. We have a four-eye principle when it comes to comparing offers. We evaluate offers based on hard facts, fixed criteria, and scoring models. But soft factors like the overall impression also play a role. Often, prices are difficult to compare one-to-one, as there are different approaches behind them. We create scenarios and try to derive a coherent overall picture. However, it’s rarely a clear decision for or against a provider, but rather a range. We emphasize this in customer presentations as well. Last week, for example, we discussed an incident response retainer. A provider was favored based on the requirements, which the customer could understand. Interestingly, this provider was even the most expensive. That shows that for us, it’s not always just about the lowest price. Our four-eye principle allows us to ask critical questions and ensure objective consideration.

Robert Wortmann: Yes, that’s a really important point. In my previous positions, when I was more independent, I also conducted manufacturer comparisons. But not on the superficial level where five features are simply listed, and one manufacturer has green checkmarks everywhere while the competitor has red X’s. No, I went deeper and worked individually for each customer. Some customers were more interested in soft facts. For them, it was more important to have a German-speaking contact person who could also provide on-site support. Others, such as multinational customers, were initially not interested at all. They wanted licenses at the right time and with full functionality. This shows how situational the requirements can be. Many comparisons don’t consider this diversity. Gartner has certainly evolved in recent years. Their reports outside of the quadrant provide more depth. However, it’s difficult when a medium-sized company looks at the same quadrant as an enterprise company. The differences are simply too great to be fully represented. So, it’s not a direct comparison, as often assumed. It serves more as an initial orientation. The issue of dependency is very important. When you search for “cybersecurity vendors” on Google, countless manufacturers appear. This image probably now has a size of at least 10 MB to fit them all. It’s incredible! Every time someone says that one manufacturer has been acquired by another and the market is consolidating, probably four new companies arise from the people who weren’t acquired or didn’t want to be. When customers ask me if I’ve included all manufacturers, I say, that’s impossible! Because in the time we conduct this comparison, three new manufacturers have already emerged. That’s why I’ve personally reviewed every manufacturer and then conducted interviews. I’ve technically verified every answer. There have been cases where I was sure I was being lied to. You get used to accepting answers here and there, but often, I realize that employees of some manufacturers themselves are not as confident in their solutions and simply accept their company’s marketing without questioning it deeper. Before I entered this world of manufacturers, my biggest fear was that I would hop from one to the other and portray each employer as the best. I try to avoid that daily and remember our story, why I’m here. But I would never claim that we’re the best in every area. That would simply not be true. In short, you’ll never be able to maintain complete objectivity because as a comparative company and consultant, you need reliable information. It’s like the debate over whether Messi or Ronaldo is the best footballer in the world. It’s probably someone who has never been professionally considered. The same can be true with security vendors.

Philipp Pelkmann: Of course, I completely agree with you, Robert. That’s why we always emphasize that our goal isn’t necessarily to find the best provider, the best offer, or the best solution. How could we guarantee that? Unlike the large enterprise customers you mentioned, in most cases, we have customers in the medium-sized sector, somewhere between 250 employees up to perhaps 15, 20,000 employees. That accounts for around 80 percent of our customer base. We work just as well with significantly smaller customers as we do with larger ones. But fundamentally, it’s the perspective of the medium-sized sector that often aims to implement a proven solution at a fair price. Here, it’s not about, as you mentioned, conducting comparisons between different solutions for months or even years, but simply saying: Which solution fundamentally fits my requirements and budget? Which partner, manufacturer, or provider brings that into the house? Do I want to work with this partner? Do I like them? Can they do it? That’s often the basis on which we work. When we talk about these comparisons, we also consider in the tendering process and selection process which providers may offer additional differentiating features and highlight those. But as I mentioned earlier, ultimately, it’s the overall picture that convinces the customer to choose a provider. This feature-based view is just one building block. Important criteria like the deployment scenario, if a customer, for example, needs an on-premises solution but the manufacturer doesn’t offer it, are crucial. Even with other, more detailed features, we look at whether the manufacturer fulfills them and how they fulfill them. Of course, there are manufacturers who always tick all the boxes, and here’s where the advantage of our platform approach comes in. We learn with every customer project, take feedback on board, and see how well a service provider performs in their incident response deployments. If someone like Kim were involved in a customer project of ours, we would ask the customer how well Kim did his job and whether they would work with him again. Naturally, we assume the answer will be positive, but for us, it’s an opportunity to learn and make this knowledge accessible to other customers. There’s no perfect selection. Even together with the customer, we can put a lot of work into it, but in the end, it’s always about reaching the best possible level of information to make an informed decision.

Robert Wortmann: Of course, I believe what’s really important, and what I often miss in the market when manufacturer comparisons are brought to me – not by you, but generally – is the lack of real project management. Honestly, I often see that the given requirements are simply accepted and not questioned before being passed on to the manufacturers. I always wonder where the value lies in that, except maybe to receive fewer emails and not be annoyed by the manufacturers afterward. That may still seem valid, but I think a consultant should always serve as an active filter. For example, a good requirement would be: “I want XDR and EDR on-premises, etc.” Of course, that’s doable, but I believe you always have to point out that there are many compromises to be made. That’s legitimate. But if you decide on this choice, then we should talk about alternatives, at least listen and discuss. If it still doesn’t fit, and you say there are still counterarguments, then we can look for a provider that only offers on-premises solutions. But let’s have the discussion first and not take everything for granted. I think that’s extremely important because it still happens too often: customers or companies set requirements without ever having a comparison with practice. I consider that extremely important, based on my own experience. In the past, I’ve managed various European countries and found that the market works quite differently, especially in the UK. It’s a very commercial market, where solutions are almost arbitrarily purchased for a year, and sometimes these solutions aren’t even implemented within that year, and twelve months later, something new is purchased again. What do you think makes the German market special? I even notice that in a globally operating company like ours, the German market functions differently in some areas. It’s not particularly agile in decision-making, which isn’t necessarily bad and in many cases even has advantages when considering other countries. But what are typically German requirements for you? Sometimes when I look at requirement catalogs, I think I could almost insert a German emoji here.

Philipp Pelkmann: It often starts with the language, the interest in German-speaking providers and manufacturers. That’s definitely a clear focus. I think that in very few cases, for example in the area of pentesting, we’ve been able to place or mediate providers outside the DACH region. In the end, there’s just a good selection in the German-speaking region. The typical German medium-sized company, as I’ve experienced it, naturally wonders why they should hire someone from the United Kingdom, Israel, or other countries when they can get the same thing here in Germany. I’ve also encountered this more often with Austrian customers who have insisted that the provider come from the region, at most perhaps from Bavaria. Of course, that depends on the context, especially when looking for SIEM providers. I think that there, in the region, you often have to search for a long time and don’t find so many options. But regionalism is certainly an important point. Then there’s something else, and I have to be honest, I’m not sure if this is typically German, but often relatively high requirements are set without a fair assessment of one’s own capabilities. A typical example is the 24/7 requirements, which are almost always included in the standard requirements for service provision. Yes, of course, round-the-clock support is in demand. We try to question that more precisely in our consulting packages, which are part of such projects, and then ask, for example: “24/7 understood. However, what about your own setup? Do you have an emergency plan? Is that defined? Who would act in your company on weekends, and what skills do you have besides the IT manager who says, ‘In an emergency, just call me on my mobile,’ to check the whole thing?” Honestly, I lack the direct comparison here because we are mainly active in the German-speaking region. But sometimes, there’s a lack of self-reflection. There’s a lack of evaluation of the actual level of one’s own performance, and often the implementation of certain solutions is overestimated. We often entered projects where the customer initially needed a SIEM solution but ultimately didn’t have the necessary capacities for its operation or monitoring. Analysts or resources for security monitoring were missing. For example, if only 0.3 percent of the capacity is available for these tasks, the question arises of how the tool can really be used. Some manufacturers advertise their solutions as low maintenance or based on artificial intelligence. However, upon closer examination, it becomes clear that an effective SIEM solution requires a dedicated team that continuously adjusts the rule set, monitors alerts, and responds to them. Without this ongoing attention, such projects often end up in a managed service or security operations center approach. It’s important to reflect on what contribution one can make in such projects oneself. Another important aspect is decision-making agility. Anyone active in this market will surely agree that projects often start under great pressure. Despite months of discussions, everything has to happen quickly. The given time is far too short from the beginning, and delays occur in the project when the customer needs to deliver something, be it a decision or a go for the next phase. Therefore, we try to design more realistic project plans to convey more realism to all parties involved. For example, if thousands of requirements exist and manufacturers are only given a short time for submission, we try to create a platform that protects both the manufacturers and the providers. This is not always successful, of course, but we strive to find a realistic approach for all parties involved because the customer is king.

Robert Wortmann: These are important points that I often observe in my practical experience. In Germany, companies tend to think very deeply and get lost in details. In contrast, this often happens far too little in the UK. Neither extreme is ideal – acting without direction due to marketing trends or over-analyzing. Many German companies have little to no qualitative data. Without data, they lack the foundation for investigations, which in turn leads to a lack of transparency and operability. Often, they try to handle each subdomain perfectly without solidifying their basic data management structures. Therefore, I like to emphasize to companies that it’s important to get asset management under control before tackling lofty goals. However, it’s also important not to fall into an endless process where you focus on perfecting asset management for six years. Instead, priorities should be set without stagnating. This often happens in Germany: companies have several projects running and hesitate to start new initiatives. I understand the situation, but when it comes to fundamental issues like building security structures or creating transparency in the company, these may need to be prioritized. Another important topic that plays a role is the 24/7 concept. Security undoubtedly needs to be ensured around the clock. But when our customers demand that their employer also be reachable 24/7, I wonder, who could we contact at night if an incident occurs? We can take basic countermeasures, but we are not able to inform your customers if your systems fail or adjust your website – that is not our responsibility. We only represent a small part of the whole. Customers then say that no one is reachable at night. From a labor law perspective, it’s not possible for us to establish permanent on-call duty – that requires months, consultations with the works council, and the like. I understand the German system, which often moves slowly, especially concerning works councils. But then, let’s at least take basic countermeasures at night. That would allow us to isolate hosts network-wise to at least do something to contain damage. Although this is not our preferred approach, it could help. No, we can’t do that because if something goes wrong and a server is compromised, it can permanently ruin the entire project. Then I say: Fine, but then it’s not a 24/7 security operations setup. It may be that someone monitors around the clock, but that’s not what we understand as a 24/7 security operation. This is an example of where it’s actually sometimes difficult. It’s a quest for the best of all worlds. High demands are made, but often there’s a lack of willingness to go the extra mile. Unfortunately, this is something I often experience. My experience shows that in the rarest cases, a single party is to blame. It’s not exclusively the customer who sets inappropriate requirements. Sometimes the manufacturer promises more than they can deliver and sells their product based on an overly optimistic roadmap. However, I have rarely experienced that the manufacturer alone made exaggerated promises and lied. Often, the actual needs lie somewhere in between when projects fail.

An important topic I want to address is: Where do these narratives come from and why do requirements sometimes align? My thesis is still that the concept of a manufacturer often wins when it’s presented to the customer first and established as the market concept. This may sound judgmental, but it’s not. Of course, as a provider, we always try to steer the customer’s mindset towards the concept we represent, as the differences in functions are often small. What I notice is that a few years ago, it was normal to speak with the customer three months before the contract renewal. Today, even if we inquire six months in advance, we sometimes hear: “Ah, we’re going in a completely different direction.” You get the impression that the manufacturer’s concept no longer fits, even without explicitly mentioning which other manufacturer is being considered. The emphasis is always on one’s own concept, even though you’ve already implicitly been given an idea. Do you also notice that even when inquiries are made, many preconceived marketing ideas are already in the minds of customers?

Philipp Pelkmann: Absolutely! We don’t always start from scratch. While we do it gladly and often, supporting the customer in developing a roadmap based on an initial consultation when the customer is still largely uninformed, the reality often looks different. The customer has already obtained offers, may have insights into the SOC, and finds it all great. Essentially, they bring us on board to validate that, to perform a reality check, and maybe to verify if the requirements really fit or if there are comparative offers, and so on. I believe one of the reasons we founded our company was the realization that, on average, manufacturers spend 41 percent of their budget on marketing and sales. This can be seen in the balance sheets, especially with American publicly traded companies – sometimes up to 80 percent goes into this area, 10 percent into breathing, and another 10 percent into the product. This creates, I’ll call it maliciously, a marketing overhead. I don’t mean that negatively because we also do marketing and invest money in it. But, yes, decision-makers are also somewhat blinded by this and consciously steered in a certain direction. From the provider’s point of view, this is completely legitimate. However, it leads to a great deal of uncertainty among many decision-makers. The question of which monitoring approach to choose is often unclear. For example, should one focus on OT monitoring if one is a manufacturing company because it’s the new attack vector of the future? Or should one do it because one might be a critical infrastructure company and the IT Security Act 2.0 requires it? Or should one continue to operate based on endpoints, where there is already an existing solution and a more modern setup is being considered? Or should one rather consider network traffic through an NDR solution? Depending on which concept was there first, one naturally also tends to think in that direction. I fully agree with you: It can often steer the customer in a certain direction. And here, in my opinion, it’s important to remain neutral and tell the customer: ‘Of course, you’re the king, you determine the direction in the end. But honestly, we might even initially prioritize something entirely different.’ Before you think about monitoring and invest a six-figure annual amount, why not sit down for a quarter and design a contingency plan because you currently don’t have one. After that, you can build it up as part of a program. I think especially the topic of marketing plays a big role here. We see this also at trade shows where we are present, such as at ITSA last year in Nuremberg. Robert, were you there too?

Robert Wortmann: No, it was rumored that I specifically went on vacation. People who know me know how much I hate trade shows. Maybe I would have had a little more time for vacation, but Denmark was just very convenient that week.

Philipp Pelkmann: It would have been much more relaxing for me too because the three days of the trade show were really extremely exhausting. This event has now become more of a fun event. You’re allowed to laugh, you’re even allowed to have a beer – but from my point of view, the marketing aspect is a bit too much in the foreground. Everything is pulled out, every possible thing is offered at each booth. Probably we’ll do that next year too. However, this unfortunately means that objective, fact-based conversations sometimes fall by the wayside.

Robert Wortmann: Yes, it’s difficult, if not impossible, especially as an employee of a manufacturer. You can criticize spending on marketing and similar things as much as you want, but in the end, they are businesses. In most cases, these are truly companies that really want to help their customers to a large extent. But of course, they also need to make money. If they are listed on the stock exchange, they are accountable not only to themselves but also to their shareholders. That’s just reality. And anyone who claims they’re only there to protect you from the bad guys is lying. We all want to make money! I want to make money, and even a customer who administers this solution expects a salary at the end of the month. We can always argue about the highs and have a fundamental discussion, but that doesn’t help. Nevertheless, I believe that both are possible. I think that a manufacturer can pursue an objective approach to a certain extent. Of course, this has its limits. But I have also told enough customers that the concept we have here doesn’t fit, that it simply doesn’t work. You wouldn’t be doing yourself any favors with it. Does this happen five times a week? No, but it has happened, and I’m glad that it does occasionally. What interests me is that I currently see manufacturers on the market who are the epitome of excellence for six months or eight months. Everyone talks about them. Whether they then really have a resounding success on the German market is another question, as the sales cycles are often too long for that. Then they simply disappear more or less completely. Suddenly, there are only two salespeople left in Germany, everything is different in other countries. You no longer see them as competition in any situation. Do you often see that too, and how do you deal with such issues in your consulting? I see it with German companies when I talk to colleagues from the UK. They are always amazed that we only do three-year deals and customers often commit to all security software for three, sometimes even five years. How do you deal with that? Because those should be long-term concepts, because if it weren’t long-term, we wouldn’t sit down together to work something like this out.

Philipp Pelkmann: I completely agree. It’s one of our main tasks to analyze the market, observe where new interesting providers emerge, then we hold discussions, look at the solutions, have demos shown to us, and so on. That’s very important. I think one limitation is that our typical customer often doesn’t think along those lines but always seeks proven, working solutions. Ideally, they want to speak with other customers who are already using this solution and acquire it at a fair price. As a result, in our typical projects, we don’t have this problem so much because we’re not constantly comparing new market entrants and ending up in a gray area where a new product from a company in Israel is pushing into the German market. It may be a great solution, but honestly, we don’t know if it will prevail or if the company will still exist in a year and a half. We’ve had such projects and then try to make that transparent based on the information available to us. That can then also be a decision criterion to say, “This manufacturer has been on the market for 20, 25 years, has many analysts and employees here in the German-speaking region. And then there’s this new, innovative solution. It promises even more artificial intelligence and state-of-the-art technology, but just as you described, there may not yet be German support and no existing customer references.” We certainly don’t have a fundamentally different view of the market. We also work our way through, and in the end, I always try to react as the company purchasing would if they had enough time to make the best possible decision based on the information. But fundamentally, it’s a big challenge, as you briefly mentioned: the constant turnover of salespeople from one manufacturer to the next. I also see this as a big problem because it often means that colleagues in the projects with the customer aren’t really informative. We just talked briefly about the manufacturers, and I fully agree: There’s a business case behind it. We have to make revenue, we want to make money, that’s completely legitimate. At the same time, in my opinion, many providers often make life difficult for themselves by using salespeople who can’t properly explain their own product or go through system houses whose representatives don’t really know the product’s advantages, disadvantages, or unique selling points. We always ask a simple question: What sets your product apart? What is the selling point? If we don’t get a clear answer to that, we think something is wrong. We also often notice that many salespeople are not adequately prepared for the conversation, especially in our projects, even though the information is usually very detailed. Often there’s no prior consultation with us to understand what the customer wants and why. I’ve witnessed many provider pitches where I think: If only they had invested the time beforehand to understand what the customer really needs. Then we wouldn’t have to start from scratch again.

Robert Wortmann: Yes, that often aligns with my experiences, even though I’m now working on behalf of the manufacturer. Sometimes it’s even hair-raising to see what’s submitted in tenders. This becomes particularly noticeable when there’s a lack of a certain locality. This is important to German customers, and it often reflects in the results. I’m not just talking about the language, whether it’s English or German, but rather about the way requirements are addressed. It’s sometimes really difficult. If you were to ask me as a manufacturer what our USP is, I’d probably say: I have no idea. In other markets or technology areas, it might still exist, but in the broad market like XDR, I believe that any USP I mention would be nullified because there’s certainly another provider offering the same. If a customer asks me about it, I might say: I don’t know, there might be one, there might not. But I’ll present our concept for the next three years, technologically and operationally. My concern is that you feel good about it, that it meets your requirements, and that we are the right partner. I want you to like the idea behind our concept, how we present it, how I’m explaining it right now. If you like this idea and if we can show you demo data – even better if we can do that with your own data over four weeks – then I don’t need a USP, and this discussion becomes less relevant.

Philipp Pelkmann: I understand your point. I see it a little differently because, for me, the USP is not limited to the technical solution itself but to the overall picture that you exactly address. We are able to create an overall concept that may be unique compared to others. Depending on the existing customer landscape in the status quo, a manufacturer may have certain advantages because many of its components are already in use. This could mean higher integration capability or better fit with the customer’s employees’ knowledge. In my opinion, one should always be able to demonstrate from these overall scenarios why we are particularly suitable here. Of course, there’s always tough competition in terms of features, and it’s fair if the customer ultimately chooses provider A or manufacturer B because they are practically equally good. But often, there’s also a story behind a particularly large partner network or excellent support. From this mix, you can highlight strengths that may not be clear unique selling points but are still relevant. I often miss substance in conversations where a system house represents the manufacturer. You can feel that they only represent the product, there’s a sales agreement, and not much more comes from it. A little more substance would be helpful.

Robert Wortmann: Have you ever experienced failed experiences in the area of comparisons and manufacturer selection? It doesn’t necessarily have to be something where you’ve stepped into the pit yourself, but generally, what have you experienced? We’ve talked a lot about general situations where things went wrong. Do you perhaps have one or two stories where things went really wrong? Can you explain why that happened and what lessons the customer learned from it? Maybe a manufacturer also learned something from it.

Philipp Pelkmann: Before I give one or two examples, I want to clarify that our intention is not to criticize manufacturers or providers. It’s important to look at this with a twinkle in the eye, as we also make mistakes every day, hopefully mostly small ones. It just happens. Once I miscalculated the pricing in a project, unfortunately only noticing after the presentation. Of course, I then had to explain to the customer that the prices would be different than previously discussed.

For this reason, we’ve introduced a four-eyes principle to ensure that important criteria are always double-checked. Nevertheless, there are occasional misinterpretations or mistakes. There were projects that were extremely attractive, in terms of customer size and clear requirements, projects that the entire industry would target. However, the sales team failed to respond to two emails within four months and only responded later, during my vacation. Unfortunately, by that time, it was too late as the customer had already made their decision based on the shortlist. That’s a story you can chuckle about.

What I mentioned earlier also relates to the provider’s unreflective approach. We had a larger project in the area of ISMS GRC Governance Risk Compliance with a great customer. However, the provider chose a smaller company that could still be considered a startup. They were flexible and agile. When I informed the tool manufacturer about the rejection, they expressed extremely negative sentiments about the customer’s decision. That was unreflective and showed that they didn’t want to understand why the customer chose a smaller provider. There seem to be obvious reasons for that decision that should have been taken into account.

Philipp Pelkmann: Another point I’d like to emphasize to providers and hope they implement concerns the complexity of their proposals. We ourselves offer a fairly simple package. Our services are documented in an eight-page Word document, including an introduction and legal provisions. We usually send out a proposal within 24 hours. But when I look at the proposals from other providers, I often see that they invest an enormous amount of time in complex proposals. In the end, they may only send the price via email, saying, ‘This is preliminary, as I don’t know the customer’s name yet and need to register first.’ But that could be roughly the cost. However, then they send a ZIP archive with twelve documents, totaling 90 pages in English. While this isn’t prohibited, would that be your first reaction if you were trying to win over a customer? In the private sector, you’d probably think, ‘This is too complicated, I’m afraid I’ll overlook something.’ We already have our expertise, but even we can’t read every line in detail. This sometimes leads to a point where we think, ‘This will be difficult!’

Robert Wortmann: Yes, that’s indeed a tricky issue, I’m familiar with it as well. It’s really a problem when working with many manufacturers. Sometimes it’s due to the individual, but often it’s due to the complex processes in the background – with price lists, bundles, and licenses that are incredibly complex within these companies, making it difficult to provide a reliable price.

I often have to defend the individual and not the company. A personal story illustrates the importance of considering long-term partnerships and concepts. Several years ago, when I worked for a consulting firm, I had a client who wanted more visibility and to establish the foundation for a future SOC. A budget was set that couldn’t be exceeded, and according to the law, a certain target was required for the needed technology. We looked for SIEM providers, but I constantly emphasized that the budget would never be enough to achieve the desired data quality and visibility with a SIEM. I always said they would be about three to four times over their budget. Although there was no comparison between the vendors and I only advised in this regard, a SIEM solution based on IPS, meaning events per second, was chosen before hiring technical staff. The provider calculated and said, ‘We have a configurator, and the result was even below your budget, plus a 15% buffer for the next three years – you’re all set.’ It was actually below the budget, maybe even 10% less, and everyone was satisfied.

Robert Wortmann: When I told them that it wouldn’t be sufficient, they said, ‘That’s factored into our three-year plan.’ But what happened? The first two analysts arrived, one with plenty of experience. He found that the firewall logs in block mode didn’t reveal much. Windows Event Logs are interesting. Please provide telemetry via an EDR tool, he said. That was calculated, and suddenly they got eight times the volume of logs. It turned out, as I had predicted, to be three to four times as much. The CFO, who was supposed to sign off on the project, was beside himself when, six months after the contract was signed, he suddenly received a request for three to four times the amount. The vendor immediately said something like, ‘Seems like he doesn’t take security seriously.’ I explained, ‘Of course he takes it seriously, but imagine you’re the CFO! Your child asks for 50 euros for the next three months, promises it’s enough, but a week later says, “Dad, I need 400 euros more and it wasn’t my fault!” That actually happened. The experienced analyst left, he had enough offers. He said, ‘What am I supposed to do here if I don’t have a data foundation? And the way projects are handled here doesn’t suit me.’ He was lucky to be able to choose his employer. That was during the probation period, and it took almost four years until they had a reasonable concept.

Philipp Pelkmann: I recognize this story in some of our projects. Therefore, here’s another explicit call to all vendors: Move away from volume-based billing models to other factors such as the number of clients or employees. This step would be truly crucial as the volume model is often not realistically calculable. We’re always happy to support in this regard. However, comparative values are important in the end to enable a better assessment. Comparable companies with a similar setup, number of users, or system diversity operate roughly in this range. But I can completely understand how frustrating it is to invest a lot of time and still not be able to implement the solution in the end. That’s really the worst-case scenario for all involved.

Robert Wortmann: Indeed, there was a lot of dishonesty from the provider in their responses, and they didn’t even make more revenue, they just let the solution expire. These are some of the failed experiences I can tell you about. Well, we’re slowly coming to an end. We’ve discussed a variety of topics today, and I hope it has helped some of you or perhaps even brought a smile to your face. With the upcoming Easter holidays, you might find yourself in one of these stories. I think nowadays you even have to mention it legally: this was not advertising or anything. I find this concept really interesting. Philipp has already talked about how there will always be limitations in one way or another and that without your own requirements, you won’t progress. You can learn from practice, that’s the most important thing to avoid operational blindness, but ultimately you have to decide and feel good about it, not someone else.

Philipp Pelkmann: If I may emphasize that briefly. We’ve talked a lot about ourselves, which of course has a certain promotional character. However, it’s important for me to emphasize that besides us, there are other providers and consulting firms, or you can build up the knowledge yourself. The comparison itself makes sense, not with the aim of pitting providers or manufacturers against each other, but to find out what I really need and which approach is right for me. Because it’s not always just about finding the best EDR solution, but also considering whether there are three other issues that a medium-sized company should prioritize. Perhaps the introduction of a second factor if it’s not already there, or updating the password length, such things are particularly important to me. All of this can of course also happen independently of our support, I want to emphasize that. It’s been really enjoyable, Robert.

Robert Wortmann: As I said, for me too. We wish you all a hopefully long Easter weekend or just tune in again. Next time we’ll have exciting guests again. We’re also planning a new episode with current news, as quite a bit has accumulated. As always, I thank you for the very positive feedback and would like to encourage you to share the podcast and rate it on your preferred podcast player. Tell it to your children, your grandparents, or anyone else – the podcast is interesting for everyone. Again, thank you very much and maybe until next time.

Philipp Pelkmann: My family will be allowed to listen to it on the way to our Easter vacation. I’m curious about their feedback on the podcast. It’s been a lot of fun. Greetings to Kim as well and until next time!

Robert Wortmann: Thank you, bye.

Listen to the podcast

Disclaimer: The podcast is only available in German

BREACH FM: https://breachfm.transistor.fm/episodes/alle-11-minuten-verliebt-sich-ein-unternehmen-in-marketing

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/de/podcast/breach-fm-der-infosec-podcast/id1641279793

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/4ooV9mM8Qiyfkj9jUkdZjj

Google Podcast: https://podcasts.google.com/feed/aHR0cHM6Ly9mZWVkcy50cmFuc2lzdG9yLmZtL2JyZWFjaC1mbS1kZXItaW5mb3NlYy1wb2RjYXN0?sa=X&ved=0CAMQ4aUDahcKEwjQ5JG8hZ38AhUAAAAAHQAAAAAQAQ

Find the podcast here: